OTL: Kermit's Song

IVERSIDE, Calif. -- The old pro could feel the earthquake 3,000 miles away. He watched the endless television reports, on two knees, wondering whether his future had suddenly become his past. He looked for familiar faces in the rubble, but ended up with a throbbing headache instead. He cringed at the thought of more funerals and woke up that first night in a sweat, flashing back to a cup of coffee that was never drunk, flashing forward to a house that never had kids. He decided there was nothing worse than an empty home. And at that moment, no home was more barren than the old pro's.

IVERSIDE, Calif. -- The old pro could feel the earthquake 3,000 miles away. He watched the endless television reports, on two knees, wondering whether his future had suddenly become his past. He looked for familiar faces in the rubble, but ended up with a throbbing headache instead. He cringed at the thought of more funerals and woke up that first night in a sweat, flashing back to a cup of coffee that was never drunk, flashing forward to a house that never had kids. He decided there was nothing worse than an empty home. And at that moment, no home was more barren than the old pro's.

The one person who had mattered most in his life was already gone. And now it seemed as if the earth was swallowing his second family whole, five at once. He had no way of calming his mind, no way of getting real news, because the phone lines were severed. But it was his gut feeling he'd seen the last of them. Three boys and two girls -- history. He decided if they were buried alive, it would be the end of him, that he would be the first man to die twice. He figured his obituary would read: "Former NFL star, 69, dies of guilt." He figured he'd just lie down and his whole remarkable, tortured life would pass in front of his eyes. Like this ...

Taming his fearsome anger

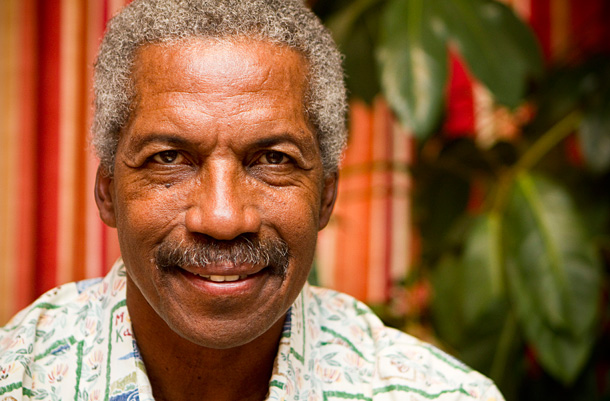

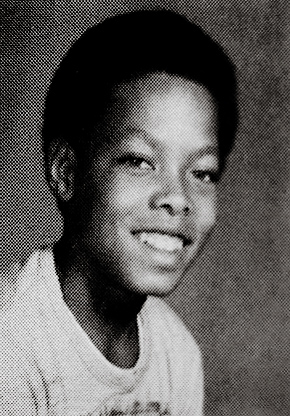

You've never seen such a kid. Fifty-odd years ago, Kermit Alexander was the whole package, the crown jewel of a crowded family. He was the firstborn of Ebora and Kermit Sr., and 10 kids later, none of his seven sisters or three brothers had his presence, his smarts, his empathy, his future.

Ebora was responsible for many of his good qualities. The family lived in the Watts section of Los Angeles, before the 1965 riots, but Ebora already could feel the tension building there. "The neighborhood needs to stick together," she told her kids, her eyes aimed directly at her oldest son. When he would jog in from school, she'd tell him to drop his books and take the 80-year-old woman down the street to the grocery store. Nobody in Watts could be left uncared for, particularly children. She'd invite random kids over for meals, no matter how many mouths she already had to feed. Her house was everyone's house, and Kermit became her first disciple.

Not that he was beyond reproach. The truth was, young Kermit had an angry side, for whatever reason. His best sport was probably baseball, but he found out early that football allowed him to hit people without repercussions. He considered it liberating, and, by the fifth grade, he was the swiftest runner, purest passer and most brutal tackler on his Catholic Youth Organization team. His father, a sturdy 5-foot-4 horse trainer, attended his games and soon realized success was going to his son's head. When a referee blew a call during a playoff game, 12-year-old Kermit slammed the ball at the official's feet. He also threw his mouthpiece, hollered at a teammate, kicked a helmet. Kermit Sr. dragged him to the sideline by a sleeve. He parked him on the bench and fumed, "You weren't trained to behave that way. You're embarrassing me. Go sit down until you can control yourself."

Ebora was stunned by the transgression, and from that moment on, young Kermit knew what to do with his temper: hide it. The next time it became an issue, three years later, the teenage Kermit had taken up boxing at the Police Athletic League. A coach wanted to see whether Kermit could take a punch, so he directed an older boxer to pummel Kermit's midsection. The coach ordered Kermit into the corner to take his beating, and each time Kermit tried to wriggle out, the older fighter shoved him back into the ropes and kept banging away. The coach nodded, let it all happen, and when Kermit finally escaped, he tossed his gloves at the coach and said "I quit." He stalked the older fighter all over Watts for a week until he saw his chance to get even -- then damn near beat the guy to death. "I must've hit him a thousand times," Kermit says. The other boxer's amateur career was ruined, and when the coach summoned Kermit's father to discuss retribution, Kermit Sr. said: "This is your fault. You have to help this young man. Because if you don't, he's going to be a killer. He has the ability to be a really, really good person or a really, really bad person. You can't do what you just did."

But Kermit had already made his choice: no more foaming at the mouth. Never, ever again. He'd seen what rage could do, how wicked it made him. He quit boxing because he feared he literally might send someone to his grave. He decided he'd play football or nothing at all, and he became a model citizen. He helped his sisters with their homework, made sure all their boyfriends treated them right. His role became protector and peacemaker, in his own household and in Watts. He graduated from high school and was recruited to play both ways for UCLA. It was Ebora's dream come true. She'd had Kermit when she was just 16 years old, and now her firstborn had made something wondrous of himself. They'd drink coffee together in the morning and talk about saving Watts. And after that -- who knows? -- maybe the world.

Taking on Lombardi, Halas and Sayers

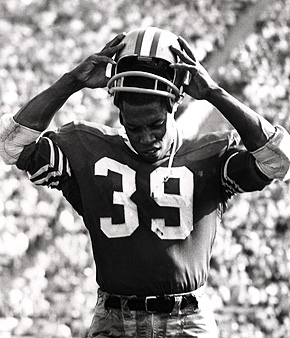

Five years later, Kermit Alexander was a San Francisco 49er, what they now call "a shutdown cornerback" in an era when the defensive scheme was "I'll cover this guy, and you cover that guy." Two-deep zones hadn't even been invented yet, so cornerbacks had to play the run or else, which was right up Kermit's alley.

Some of the league's coaches considered him a head-hunter -- Vince Lombardi and George Halas to name two. One Sunday in the mid-'60s, Kermit leveled Green Bay quarterback Bart Starr near the Packers' sideline, and the legendary Lombardi literally ran on the field to call Kermit a dirty player. Kermit's instinct was to punch Lombardi in the mouth. He had begun to raise his fist when Ebora's voice entered his head: Under control, under control, under control. Suddenly calm, Kermit just said, "Ol' man, get off my field. That's your office over there."

After the game, Kermit -- still channeling Ebora -- felt guilty about mouthing off and sought out Lombardi. "I'm sorry, Coach," he said, to which Lombardi answered, "No, I was wrong. I had no business being out there." All was forgiven, but this was the constant war in Kermit's head: calm versus pissed, good versus evil.

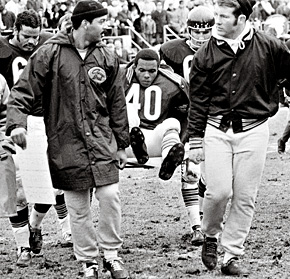

Then came Nov. 10, 1968. Kermit was an All-Pro that season, and in a game at Wrigley Field, the Bears made the mistake of running the elegant Gale Sayers to his side of the field. Kermit went airborne to take out the lead guard, but the guard dove away from him to avoid contact, which left Kermit flying straight into Sayers' right knee -- just as Sayers was planting his leg.

"It just blew his knee all apart," Kermit says. "It was sickening to hear."

Sayers' leg was just dangling. Kermit heard Sayers crying and helped drag him to the sideline. But along the way, Kermit caught Halas' glare and handed the running back over, saying: "Hey, old man, come get this one and send me another because this one's all used up." Halas flat-out started cursing at that point.

After the game, Kermit visited the Bears locker room to tell Sayers he was sorry -- more guilt. But he was vilified publicly nonetheless. Sayers was already wildly popular; then, in 1971, the movie "Brian's Song" would make him iconic. The film showed Kermit's hit in slow motion and told the story of how Brian Piccolo replaced Sayers and then nursed Sayers back to health before Piccolo died of cancer. If there was anything close to a villain in that movie, it was Kermit. He received a death threat from a Bears fan; he couldn't live it down.

But his 49ers teammates knew better. In their locker room, few were as revered as Kermit. He was never intimidated by management and would gladly show teammates his contract so they knew what kind of money to ask for. To this day, players from that team thank him for their nest eggs.

Kermit knew the Ebora in him was causing him to help. Deep down, he was still the kid from Watts, and he says the greatest moment of his career was being traded home to the Los Angeles Rams in 1970 because then he could be around his family 24/7. He'd been away in San Francisco for seven seasons, but now, post-riots, he'd get to see how his old neighborhood was faring.

The answer: not well.

Gangs were everywhere, and they were more violent now. They were recruiting in junior high schools and even grammar schools, looking for badasses. If a kid didn't have a dad, the Crips gladly played the role. Gang members bankrolled kids, lent them cars, let them have sex with Crippettes. Kermit talked to people in the streets; he knew why the young kids were straying. So he and one of his brothers-in-law co-founded a Pop Warner football team, the Watts Wildcats. Kids who were on the fence could play football instead of gangbanging, and Kermit even brought his team to Rams games to show them what was possible.

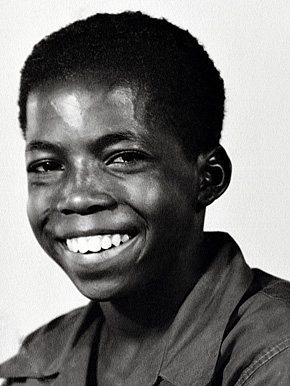

In the early and mid-'70s, Kermit went to as many Pop Warner games as he could -- it was cleansing -- and one player stood out to him more than any other. The kid played for another team in South Central L.A., and although the player was only about 8 years old and 4-foot-nothing, he kept winding up in the end zone. He was swifter, more instinctive and more physical than anyone else on the field, and, frankly, he reminded Kermit of himself. And when Kermit saw the kid's temper, he had a full-on déjá vu.

At one point in a game, this kid -- Tiequon Cox -- spiked a ball after a bad call, then picked it up and threw it at the referee. He punched a teammate in the back for missing a block and cursed his coach for not finding better linemen. Eventually, he had to be physically dragged off the field, and someone in the stands told the kid to put a sock in it. Tiequon nearly climbed the stairs to fight.

It hit home for Kermit. Twenty-odd years earlier, he'd had his own meltdown, with his father yanking him off the field. This kid needed an intervention, too. Up in the stands, Kermit rose up and proclaimed, "Somebody needs to do something with that kid, he's too good a ballplayer to be like that. Somebody ought to help him."

Everyone nodded, but not one lifted a finger, Kermit included. Had Ebora been at the game, he says she would've ordered him down to the field, and he would've said, "Yes, ma'am." He would've gone to the sideline to assist the coaches, would've tried to be a friend to the kid. He would've driven to the kid's school and checked in with his teachers. He would've become a mentor, would've taken him to meet other pro players, would've kept daily tabs on him.

Instead, Kermit did nothing. "I was a star," he says. "I had too much to do. All I did was talk about it. I didn't check in with anybody. I left."

Worst decision of his life.

A most distinguished mama's boy

Ten years later, Kermit was leading a distinguished life. He had been president of the NFL Players Association. He'd coached high school football. He'd been a local probation officer. He was a commentator on UCLA and L.A. Express radio broadcasts. He and his wife were raising two children, and he continued to be philanthropic in his spare time.

He didn't live in Watts, but he wasn't avoiding the place, either. His mother still kept her home there. She and Kermit's dad had split up while Kermit was in college, and the Alexander kids kept begging her to move to Ladera Heights or somewhere on the West Side. But all of Ebora's friends were in Watts, and she still loved making peanut butter sandwiches for kids in the neighborhood. She'd tell people her hugs went a long way there, and she resisted everyone's obsession with her moving.

Kermit felt it was his duty to go see her at least once a week, so early every Friday morning he'd slip into her kitchen for a cup of coffee. The two of them had been having these rendezvous since right before college, and Kermit always left feeling reinvigorated.

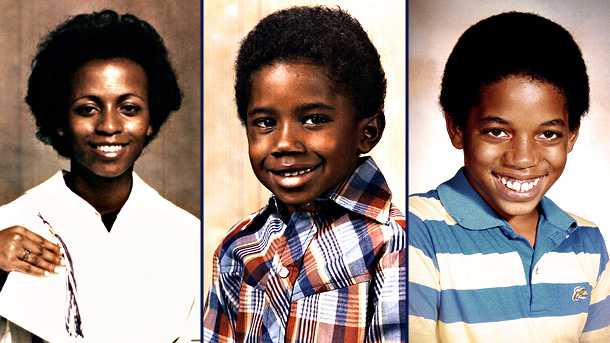

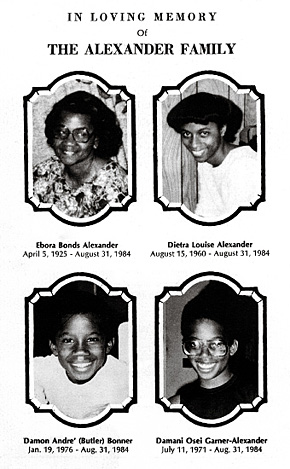

In the summer of 1984, the family was actually glad to have her in Watts because the Olympic Summer Games were being held only 30 blocks away, at the L.A. Coliseum. And late that August, 59-year-old Ebora invited several of her grandkids over to stay for a long weekend, so they could walk down South Flower Street and collect Olympic pins. Now it was just like old times because her house was bustling. Ebora's youngest daughter, 24-year-old Dietra, was already living in the front bedroom, and her 34-year-old son Neal, who was on disability, was already living in a back bedroom. But the arrival of Ebora's grandsons -- 8-year-old Damon, 13-year-old Damani and 14-year-old Ivan -- made it a true home again. Damon and Ivan were the sons of Kermit's sister Daphine, and Damani was the son of Kermit's sister Gerry, and before the sisters would leave for the evening, all eight of them would eat a jovial dinner together. Ebora -- whom everyone called "Madee," short for "Mother Dear" -- adored playing hostess.

Kermit had stopped by Aug. 29, two days before the Olympics' closing ceremonies, to see how the group was doing, and he particularly remembers not being able to leave Ebora that day. He had a business meeting to attend, and after she walked him to his car, he kept driving around the block to come back and see her on the front porch.

"Well, go on," she told him. And he tried. Once, he made it 10 blocks down Flower Street but drove back again.

"What is wrong with you?" Ebora asked.

"I don't know, I don't know," Kermit answered.

"Listen, I love you. You go take care of your business, and I'll talk to you later."

Then she blew him a kiss goodbye.

Tragic turn

Aug. 31 was a Friday, which meant Ebora was up early at about 5 a.m., brewing a pot of coffee, waiting for Kermit.

At about 5:30, her front door opened, and the wrong person entered -- an 18-year-old stranger with a rifle. He walked into Ebora's kitchen and shot her three times in the head just as she was turning from the refrigerator to put cream in her coffee. Next, the gunman entered a sitting area where Damon and Damani had been sleeping in a twin bed. Damani, awoken by the noise, apparently tried crawling under the bed before he was shot and killed. Damon never woke up and took a single gunshot to the forehead. The intruder then went into the next bedroom and executed Dietra, shooting her in the face while she was still under the covers.

At that point, Neal -- who'd been sleeping down the hall -- entered Dietra's room to leap on the shooter's back, while 14-year-old Ivan hid in a closet. There was a struggle, and the shooter apparently landed awkwardly on a red trunk by the door. A second intruder, the gunman's lookout man, ran to their getaway van, and the shooter punched Neal in the face before following his accomplice out. Neal exited through a back door, got to a phone and called his oldest brother.

"Kermit, why did they do that?"

"What did they do?"

"Why would they mess up Mom like that?"

"Neal, what happened?"

"Mom's been shot."

"Oh my God. Call the police. I'm on my way."

Kermit wasn't first to the carnage. Ivan had rushed out of the closet to call his mom, Daphine, telling her, "Something bad's happened to Madee." Daphine then called her sister, Joan, who was a sergeant in the JAG Reserve military unit. By the time Joan arrived, the house had been cordoned off, and Joan was caught by local news cameras trying to force her way through the front door. "This is my mother's house! I have a right to be in here!" she said, sobbing to the police. She and the other family members were then ushered to police headquarters, still unsure of what had taken place.

Kermit was already in a back room at the station, comforting Neal. As the oldest son, Kermit had been asked to identify the bodies, which were barely recognizable. Kermit was in a daze. But he was still determined to play the role of family protector … until he actually saw his family.

"Kermit's face looked so horrible, so sad," Joan says. "I knew something bad had happened. But I had no idea it was that bad. And then they said all of them were dead, and I'm like, 'What do you mean all of them are dead?' I just lost it; I was pounding on this filing cabinet, and Kermit was just speechless. He was on a bench … my big brother … and I just looked at him and said, 'Why?' I just screamed. And I started crying. He was so pained, he couldn't even hold me. His arms were just, like, hanging."

He was similarly numb at the funeral, although he did take charge that morning and insist the caskets stay closed because of the brutality of the murders. The family was still confused as to why its mother's house had been a target, and those who were still alive wondered whether the gunmen would kill them next. Joan, for one, began sleeping on her floor, facing her staircase, with a revolver under her pillow.

Kermit had no answers for any of them, and once Ebora was buried, he began to disappear every night after dark. His family had no idea where he was -- and never would have guessed it.

He was roaming the streets of Watts. Looking for the killers.

Looking for revenge in all the wrong places

The temper was back. His father had told that boxing coach 30 years earlier that Kermit might be capable of killing someone. Now Kermit was going to prove it.

He spoke to his friends in the streets, friends who might have heard who had pulled the trigger on Kermit's family. Watts was a compact community, and Kermit found out that members of a gang, the Rollin 60 Crips, had been bragging about "blowing a bitch's head off."

He says he "went crazy." His head was on fire. All he could think about was that he had overslept the morning of the murders, that he should've been sipping coffee with Ebora when the shooter walked in. Maybe he would've been killed, too. Or maybe he would've saved his mother with his bare hands.

He bought a pistol and decided he was going to wipe out the Rollin 60s, one by one, two by two. "Whatever it took," he says. "It was the wild, wild West all over again. I was in a murderous rage. I was very, very quiet, but I'd determined that my life was over and I was going to get rid of them. I would've killed them all or gotten killed in the process. Nobody else was going to suffer again because of them."

He says he walked the streets for six months, looking for his mother's killers night after night. He'd grown up there. He knew whom to go to for information. Some of his informants he threatened, some he begged, some he paid. But he couldn't find anybody to turn his murderous rage on.

Finally, he received a call from a former high school classmate who was working as a juvenile probation officer. A kid had confessed to hiding the murder weapon from that morning. This kid hadn't done the killing, but he knew exactly who had.

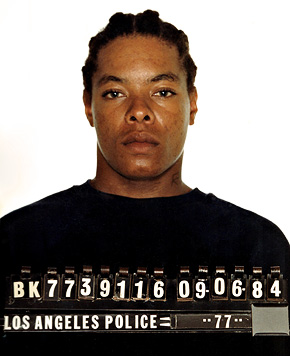

Someone named Tiequon Cox.

Consumed by guilt

The name meant nothing to Kermit. He couldn't place it, didn't recognize it. But the information was forwarded to the cops, and they discovered Cox's palm prints on the red trunk in Dietra's room.

At his trial in late 1985, details emerged about the young man's life. Cox had been abused by his mother, Sondra, and although his attorneys did not get overly specific in court, his juvenile report -- plus his mom's arrest records -- showed she had been a heavy drinker and a prostitute. At age 4, he'd witnessed her try to kill his sister, and at age 5, he'd watched her attack a police officer with a knife. Then, at age 8 -- the age at which he would have been playing Pop Warner football -- his mother allegedly set fire to his grandmother's house, where Cox had been staying.

By the time the kid reached Horace Mann Junior High School, he'd joined the Rollin 60 Crips, who, in a sordid way, became his new family. The jurors heard all of this. They heard how Cox dropped out of the ninth grade, how he then robbed three students and hit one of them with a mop handle. They heard how he pointed a gun at a mother who was waiting for her child outside the school. They heard how he stole the woman's car and led police on a high-speed chase for 30 minutes before hitting a telephone pole.

They heard the prosecution describe how Cox fell deeper into a life of violence. They heard how, at age 18, he and two other gang members had been hired to murder a family in Watts. Apparently, a girl had been paralyzed in a shooting incident at a local bar, and her family was suing the bar's owner. The bar owner wanted to eliminate the lawsuit, so he hired the gang members to assassinate the girl's entire household. The bar owner wrote the family's address on a piece of paper, but Cox and his accomplices misread it. So they barged into the wrong house -- the home of Ebora Alexander.

Periodically, Kermit showed up in court. As he listened to the case unfold, it took everything in his power not to jump over the railing and pummel the kid. Prosecutors were pushing for the death penalty, and as the family heard more and more about Cox's life, Kermit's sister Mary -- who helped run Kermit's former Pop Warner team -- pulled her brother aside.

"Do you know who that kid is?" she asked.

Kermit hadn't the vaguest idea.

"That's the kid that was always in trouble in Pop Warner. Look at what he's done!"

"Oh my God."

Kermit could barely breathe. He wanted to turn himself in to authorities. He had neglected this kid a decade earlier, and now Cox had shot four of his loved ones in the head. Kermit blamed himself, decided he'd been, in some ways, an accomplice to his mother's death. "The realization was like white heat," he says.

Even when Cox was found guilty and sent to death row in San Quentin State Prison, Kermit found no consolation. His marriage was failing because of neglect, and he was on the verge of divorce. He'd lost his radio gigs. And even some of his brothers and sisters were suspicious that Ebora had been murdered because of Kermit's business dealings. Just before the attack, Kermit had pulled out of a horse-breeding contract, and one of his brothers-in-law heard that he had made enemies in the process. None of this was related to the murders, but there was finger-pointing by the family, and Kermit felt like a pariah.

In the late 1980s, he packed up and moved an hour away to Riverside, Calif., to live near his father, who had taken ill. He'd never had a chance to say goodbye to his mother, and he wasn't going to risk that happening with his dad. He wound up coaching youth teams here and there, moving from mindless job to mindless job. Worse yet, he was still racked by guilt, was still blaming himself for turning his back on Cox in Pop Warner.

"It was paralyzing," he says. "When my mother died, the lights went off in my life. I ceased to exist as a person. I was at the bottom, on an island, trying to survive, trying to figure out what to do with myself."

Then he got a phone call from another Ebora.

Mom 2.0

Her name was actually Tami Clark, and, he'd realize later, she was like his mother reincarnated. Tami was 20 years younger than he was and one of those people who has never met a stranger in her life, just like Ebora. She did charity and volunteer work for the Chamber of Commerce in Mammoth Lakes -- five hours north of Riverside -- and in the summer of '91, she happened to need a grand marshal for a Fourth of July parade.

One of her friends, former Dallas Cowboys kicker Efren Herrera, suggested Kermit.

"Who?" Tami asked. "Is he any good?"

She ended up offering him the gig over the phone, and Kermit accepted for the sole purpose of taking a much-needed vacation. He had nowhere else to go, no family to picnic with. But as soon as he met Tami, he thanked his lucky stars.

Inside, she was almost as broken as he was, unhappy in her marriage and burying herself in work. But she was also a master at hiding it and made it her mission to hear Kermit belly-laugh. She could tell immediately he was closed off, so she talked his ear off and urged him to make himself at home. He asked her how to "turn on" the microwave in his suite, and she joked, "Just say 'Ooooooh, baby, ooooooh, baby.' " He doubled over, and remembers thinking it was his first laugh since the murders, remembers thinking he needed that.

After the parade, they went their separate ways, until Kermit heard Tami had moved to nearby Temecula and was getting a divorce. They had a dinner date, which led to a second dinner date, which led to a third. Tami was intrigued.

One night while watching TV at home, she stumbled upon "Brian's Song." She had enjoyed the film from way back, because of the love story and because she went to Baylor right after Mike Singletary played there and became a full-on Chicago Bears fan. But she had never paid much attention to the football scenes -- until a certain No. 39 came on the screen and tore up Sayers' knee.

She covered her eyes and then called Kermit. "Hi, I just watched 'Brian's Song.' Are you the one that hit Gale Sayers?"

"Um, yes."

"We're through. Don't ever call me again." And she hung up.

She was joshing, of course -- that's Tami -- but Kermit thought, "Oh, no, here we go again." He was in such a dark place that he believed her. He'd have believed anything at that point. He remembered the death threat he'd gotten because of the Sayers hit; it was all still a sore spot for him. People forget he carried Sayers off the field, that he went into the Bears' locker room to apologize. He called Tami back and said, "Gale Sayers is not going to break up my relationship with you." She began to giggle, and, finally, he started to figure this woman out.

By the end of 1992, they were living together, although there was still some sort of wall between them. He admits they were "intimate, but not close," and the reason was Aug. 31, 1984. He always was vague when she asked him about his mother; she could never get a direct answer. They would be out in public and someone would pull her aside and say, "Oh gosh, I heard about your husband." They weren't married, of course, but her only response would be, "You mean about his family?"

She went to the library -- this was pre-Internet -- and searched through microfiche from 1984. She read every article and found herself weeping. Later, she and Kermit were driving on the freeway to see her parents in Anaheim when she said, "Every time we go somewhere, somebody asks me about your family. One day, when you're ready, could you tell me, from start to finish, what happened?"

He had never discussed the murders with anyone outside his family -- and hadn't planned to. He floored the car and exited the freeway. She thought he was going to crash the car on purpose and kill them both, but instead he slammed on the brakes and pulled into a deserted parking lot. Then he dumped it all on her.

His opening line was, "OK, I'm going to tell you this one time, and you can't interrupt me or ask questions because this may be the only time I tell this story." More than four hours later, he was done, sobbing like a child.

The moment bonded them, and they ended up staying together for nine years. At first, both had been burned out on marriage, but as time moved on, Tami wished he'd put a ring on her finger. The problem was, he still kept her at a safe distance. He comforted her when she lost her stepdad, and she comforted him when he lost his father, but in the aftermath of these sad events, they'd go to their separate corners. Tami was still hoping, perhaps blindly, that he would open up to her and propose. But Kermit wouldn't go there. He'd be preoccupied with get-rich-quick business deals, all of which failed, or he'd withdraw and spend hours at the golf course. By 2001, they were polar opposites. Tami was embracing religion, while Kermit -- the grandson of a pastor -- couldn't trust any God who would allow the brutalization of his mother, sister and nephews. So Tami moved out.

Kermit became a drifter. He moved to Oklahoma to co-found a Thoroughbred horse racing syndicate, largely because horses had been his father's passion, and a barn was now the closest thing he had to family. But the business failed, much of his football money was gone and he remained a transient, living out of his car. He couldn't even commit to a drawer. He eventually caught a flu bug that wouldn't go away -- a sore throat, red eyes and a hacking cough that stayed for weeks. He was 60 now; this was potentially dangerous. The flu turned into pneumonia, and he actually believed that the illness suited him, that he somehow deserved it. He wasn't dead, but his eyes were dull, and all he wanted to do was sleep.

And then, one night, Ebora came to him in a dream.

What is found becomes lost

Maybe it was the flu medication he was on, but Kermit is adamant that he heard his mother's voice while he was sleeping. He says she scolded him for feeling sorry for himself and urged him to get back to being a protector, a provider. She also told him that if he didn't return to his roots, he wasn't going to live another year.

Instantly, Kermit thought of Tami. They had been speaking over the phone every two or three weeks while he was in Oklahoma, and he was always reminded how much her voice -- the pure energy of it -- cheered him. By now, he was over the pneumonia and taking stock of his life. He asked himself, "What am I going to do about Tami?" and realized the happiest he'd been since 1984 was with her. So, in the spring of 2003, he moved back to Riverside.

They met for coffee, and she broke the bad news: She had met somebody else. Kermit called her the next morning at 4:30. She could tell he'd been crying. She asked him whether he was OK, and he said, "No … Has this man asked you to marry him?" Tami answered, "Not at all." But she was livid. She sensed this was a competition to Kermit. "I've waited all this time for you to engage, and you wait until I start dating?" she asked. He told her that he'd had an epiphany, that he needed to come back and make it right. She told him they would talk later.

That same spring, Tami committed to a 250-mile charity bike ride and needed someone to train with. Her boyfriend wasn't interested; Kermit was. They spent hour after hour at nearby Lake Perris, riding the trails and talking on park benches. He was finally an open book, finally sharing his guilt over Tiequon Cox. There was a reconnection, albeit not a complete one. Tami was immersed in her church, and Kermit was still unable to believe in anything spiritual. In September 2003, she told him she was going to Haiti with a Christian radio group to see whether she could make a difference there.

She left without him.

Sometimes you have to go far away to find yourself

As Tami stepped off the plane in Haiti, she could "smell the poverty." The sewer systems were backed up, and trash was decomposing in open bins. On top of that, the temperature was an oppressive 90-plus degrees.

She noticed water flow down a public irrigation system at the side of the road and watched pigs and oxen defecate in it. She saw a man wash his motorcycle in it, as well. Farther down the stream, she saw a woman using the water to prepare a meal. Others were bathing in it. Tami had to turn away.

There were no tropical breezes, only gusts of stench. She said to herself: "God, you've picked the wrong person. I can't change this. I have nothing to offer here. You need someone rich who can write a check and hire a construction crew. God, why am I here?"

Her group was taken to the Mission of Hope in Titanyen. She expected more hopelessness, but was stunned by the sight of 1,200 kids lined up for school, wearing color-coordinated uniforms. She was told that 35 American pennies could provide a child with one meal a day. She began to feel reassured. The mission's director, Brad Johnson, took them three-quarters of a mile up a hill, off the main road, to show them land he hoped to turn into a village. That high, looking over the Caribbean, Tami finally smelled fresh air. The heat and wind reminded her of her grandmother's home in Amarillo, Texas, where windmills were used for power. She asked Johnson whether anyone had discussed a windmill project at Mission of Hope, and he said someone just had. Her light went on; maybe she could contribute.

Johnson walked them down to the Mission of Hope orphanage, which housed 47 homeless children. Tami was unsure of what she would see until -- out of the blue -- an emaciated boy, about 5, walked up and poked her on the arm. He called her "Mom."

Tami's jaw dropped. She figured this kid, Clifton, called all woman visitors "Mom." Besides, Tami had already been a mom, had a grown 23-year-old daughter from her first marriage. But he kept poking her, kept calling her "my mom," and when Tami ran into Johnson a while later, she said she'd bumped into Clifton.

"Yes, everybody meets Clifton," he said, laughing.

"Oh, that explains it," Tami said. "Because he kept coming over saying he wanted me to be his mama."

"What? He never does that. Are you sure it's Clifton?"

Johnson asked Tami to show him the child she was talking about. She pointed to Clifton, and Clifton then ran straight at her, leaping into her arms. Johnson was astounded.

Tami wanted to know more about the child, and Johnson explained that Clifton had been brought to their orphanage, near death. He'd been malnourished and had a distended stomach because of worms. He had scabies, as well, on both feet and arms, and all his hair had either fallen out or turned orange because his scalp had lost all pigmentation. His nails wouldn't grow, and his teeth were decaying. Johnson said he had looked like a 90-year-old man and had been given about a month to live.

The orphanage ended up nursing Clifton back to health until he fell and broke a femur weakened by a lack of calcium. But, even then, his doe eyes and giant grin ingratiated him to everyone. By the time Tami showed up, his health had stabilized, and she asked whether she could take him to town with her and let him swim at her hotel pool. By the end of her six-day visit, Tami and Clifton were inseparable.

On the day she had to leave, Clifton refused to look at her and began wailing. Tami's heart ached. She told him, "Clifton, look at me. I'm gonna be back. I'm coming back. You've got to believe me."

He wouldn't acknowledge her, wouldn't even watch her drive off. He figured he'd never see her again, that she was like all the others. No one ever came back to Haiti. No one.

Saved by a bold 5-year-old

Kermit was waiting for Tami when she returned to the States. He invited her to Lake Perris, sat her down on a bench overlooking the water -- and asked her to marry him.

Her answer was no. He couldn't believe it. Before their breakup, she'd been dying for him to put a ring on her finger, and he wanted to know what had changed. She mentioned her trip to Haiti, told him that she had met a little boy who'd worked his way into her soul. She said she was going to make that child part of her life, some way, somehow, and she was going to dedicate herself to bringing windmills to Haiti and other Third World countries.

She loved Kermit, but she needed them to be on the same page. She began to describe Clifton to him -- the little taps on the arm, him calling her "my mom." She said, "Kermit, come to Haiti with me. I'll introduce you to Clifton, and you can be part of it. If this is something you want to do, then ask me to marry you again."

In January 2004, they flew down together. When they arrived at Mission of Hope, Tami rushed inside to find Clifton while Kermit waited anxiously near their van. He then saw a little head peek around the corner of the building, a boy who looked to be sneaking out of the orphanage. A second later, the kid bolted past Kermit toward some other kids playing soccer.

"Clifton!" Kermit shouted -- somehow guessing it was him.

Clifton stopped on a dime, turned, took two quick steps and jumped into Kermit's arms.

"It was so natural, it was unbelievable," Kermit says. "I just called his name out, anticipating he'd maybe stop, say hello, shake my hand. But he just ran into my arms, a big grin on his face, just chattering like he had always been there. It was the most comfortable thing. That was the point when I completely let go. I was OK. I had healed. I had the faith and courage to go on with my life.

"There was a reason to live now."

Instant family

Kermit and Tami were married in May 2004, at Lake Perris. For their honeymoon, they flew to Haiti.

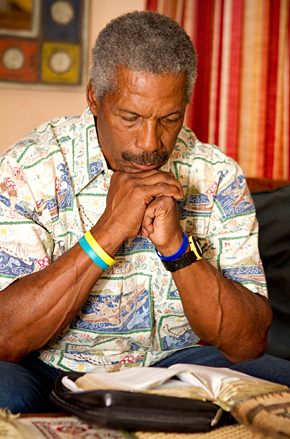

Their sole objective was to adopt Clifton, and Kermit was going to stop at nothing to get it done. Every morning, from the moment he'd met Clifton, he'd woken at 4 or 5 in the morning to say a prayer. He would close his eyes and whisper: "I hope I don't miss anybody today. … I can't miss someone and have them turn into Tiequon Cox. Please, Lord, don't let me miss Clifton. Please don't let me miss anyone again."

He was a new man all around. Tami had put Kermit in touch with her pastor, Tom Lance, and Kermit reopened his relationship with God. The events of 1984 came up in their private sessions, and Kermit made peace with his nine siblings and somehow was able to forgive Tiequon Cox. By now, the killer was nearly 40 and still on San Quentin's death row. He'd become notorious at the prison for stabbing the original Crip Stanley "Tookie" Williams in 1988 and for also trying -- and failing -- to escape from San Quentin in July 2000. But Kermit says he spoke to a prison official who told him that, over the years, Cox had finally learned to be less volatile. The old pro no longer itched for Cox to be executed. He saw the bigger picture.

He and Tami were now in spiritual sync and, by the end of 2004, they'd flown to Haiti six times. Part of it was to begin their project, "Operation Windmill," but a lot of it was to parent Clifton, to get the adoption rolling. Fairly soon, though, there was a hitch: Clifton wasn't available to be adopted. Johnson told the couple that Mission of Hope's goal was to raise children into strong, educated, Christian citizens, creating a more self-sufficient Haitian society. Tami and Kermit couldn't argue with that, but asked to stay in the child's life. They sent Clifton $300 a month, bought him clothes, covered his medical costs. Clifton started calling Kermit "my dad." There was nothing that could keep them apart.The only downside was that whenever Kermit and Tami would leave, Clifton would sink into a major depression for months on end. He wouldn't eat. He'd fall ill. The couple would try to cheer him up from long distance, but telephones were scarce at the orphanage. One day Tami dialed the cell phone of one of Clifton's role models -- a 20-something orphan named Thony Durand -- and luckily found Thony playing soccer with Clifton at the time. When Thony told Clifton that Tami and Kermit were on the line for him, the boy kept excitedly repeating, "Pour moi? Pour moi?" Kermit started to cry.

By this point, the orphanage was concerned about Clifton's emotional state, and one day when Johnson was in the U.S., he pulled Kermit aside for a candid talk.

"I have to ask you and Tami to stop coming," he said. "Because he falls apart after you go. It has put his health at risk."

Kermit swallowed hard.

"Or," Johnson said, "you'll just have to adopt him."

Kermit's heart was pounding, and he raced to call Tami. She wept at the news, and he felt like passing out cigars.

They were gaining a son.

Instant family, only bigger

The adoption paperwork was endless, and they had to somehow find Clifton's mother for approval. They knew she was still alive, but she could've been living anywhere in the country. What's more, Haitian adoption policies seemed to change direction every time the wind blew. By 2005, Clifton was still in the orphanage.

But Kermit and Tami were resolute and began planning for their life with Clifton. They found a one-story, three-bedroom house on a cul-de-sac in Riverside with a horse stall and a swimming pool. It wasn't elaborate or brand-new, but it had nice acreage in the back and a dirt basketball court. To a young man from Haiti, it would seem like the Taj Mahal.

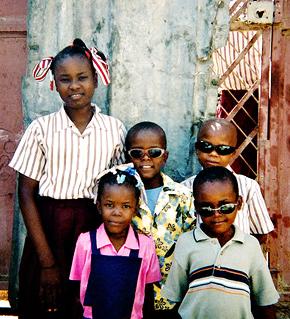

On one visit to see Clifton, the couple wanted to deliver food and clothes to other orphanages around Port-au-Prince. Clifton asked to be their tour guide and directed them to the Good Samaritan orphanage in Cabaret. There, they noticed Clifton hugging and high-fiving four of the children there: two boys and two girls. They'd never seen Clifton this attached to other kids before, so a curious Kermit asked him, "Who are they? We would like to meet your friends."

"It's not my friends," Clifton said in his fractured English. "It is my brothers and sisters."

Tami and Kermit were floored. They had no inkling these kids even existed. A moment later, the oldest boy of the group, Jameson, touched Tami's arm, asking whether they could all have a picture taken with Clifton. "Because you are taking him away to America," Jameson said, "and we will never see him again."

Tami then looked at Kermit, who had tears in his eyes.

"We can't do this," Kermit said.

"What do you mean?" Tami asked.

"We either take them all or we don't take any of them," he said.

"I know," she said. "They're still invested in each other."

"Then we take them all," Kermit said.

"Are you serious?"

"We take them all."

Did somebody say 'instant'? Well, not exactly

Twenty-one years earlier, Kermit had lost four family members. Now he stood to gain five.

He and Tami began to fly to Haiti every two or three months, 10 days at a time, desperate to find the kids' mother. They got a tip she was in a homeless shelter, at a church, and Tami says they found her lying down, "looking almost possessed … looking 30 years older than she was." The woman had brain damage from malaria, and they learned Clifton and his brothers and sisters had been sent to the Good Samaritan orphanage after she had become ill. Tami and Kermit approached the woman respectfully and asked her to OK the adoptions. If she'd been capable of caring for the five kids, it might have been different. But she seemed thrilled to sign the paperwork.

The years crawled by, and every time the adoptions seemed to be progressing, there would be some kind of major calamity -- a hurricane or an election followed by a riot. Clifton was well cared for at Mission of Hope, but in an attempt to give the other four kids stability, Tami and Kermit enrolled them in a more upscale boarding school, the Haitian Academy. The cost was $30,000 a year for the four of them, but each child had a nanny to look after his or her needs. It was the only way the couple could stay sane.

Still, Kermit was buoyed by the fact that whenever he and Tami visited Haiti, the kids called them "Mom" and "Dad," and never anything else. Back in the States, he and Tami had moved into their new house and already had begun decorating the children's bedrooms and planning who would room with whom. They knew they would need a longer dining room table, knew they would need a van. Kermit liked the anticipation of it all. He would close his eyes and daydream about a crowded house, just like the one he'd grown up in with Ebora. His nine siblings, the ones he'd always protected, told him they were there for him, that they wanted him to keep fighting for his five kids 3,000 miles away. It warmed him.

But the wait was excruciating. They each had jobs to help keep their minds off of the ordeal -- Kermit was a community service officer at Riverside Community College and Tami continued her charity work and fundraising. She also had a lucrative gift basket business -- which had previously provided the couple with a nice windfall -- but the recession in the U.S. eventually took a financial toll on Kermit and Tami and they had to pull the four kids out of the Haitian Academy. They moved them to HIS Home For Children, an orphanage in Port-au-Prince that, on the plus side, had better success getting kids adopted.

But nothing sped up. The couple would grow frustrated with their adoption lawyer, or with the instability of the Haitian government, or just by time, ticking away. Kermit turned 69 on Jan. 4, 2010, and there was still little advancement and little hope. Status quo was a bear.

And then the earth moved.

A monstrous earthquake that changed everything

In the early afternoon of Jan. 12 of this year, Tami was driving on Interstate 15, listening to her car radio. A special news report came on, and the next 15 seconds changed her world.

There had been a major earthquake -- 7.0 magnitude -- in Haiti. Mass destruction. No telling how many were dead. Tami remembers having "the life sucked out of me. I couldn't breathe." She called Kermit and instructed him to turn on the TV. That's when the old pro thought his life was over … a second time.

She pulled into the driveway of their home -- their kids' home -- and they hugged and wept. He assumed the kids were all dead, or at least the four in Port-au-Prince, only six miles from the quake's epicenter. He and Tami had been in Haiti just six weeks earlier, and over dinner with friends, she had asked, "Has Haiti ever had a major earthquake?" The answer was "not for about 200 years," and she'd been relieved because the construction was so pitiable there. The cement was porous; there were no building codes. Haitians were more worried about looting, thieves and hurricanes. So, as the news began pouring in, they couldn't help assuming the worst. Three million people were living in an area originally meant for 50,000. The casualties had to be extreme.

Tami called every Haitian phone number she knew, but the lines and signals were all down. They couldn't just march down to Haiti and start digging. They weren't made of money. Their 20-plus trips to Haiti had sapped much of their savings, so they were at the mercy of their friends for information, for news about who died and who lived.

For four days, Kermit parked himself in front of their television set. He saw horrific scenes of people leaving buildings with their limbs missing or torn apart. He hoped his kids hadn't suffered that way. For four days, he couldn't sleep. For four days, he imagined five funerals and then a sixth: his own. Kermit would sit in his study or on his back porch at 5:30 every morning and say to himself, "If they don't survive, then what am I needed for? I have a purpose in them. They are my salvation. And if they aren't here, then why am I here?"

On the fourth day, Tami finally reached one of her key contacts on the phone. She asked him whether he'd heard from any of the Haitian ministries, and he told her to give him a few hours. She and Kermit got down on their knees and waited. "And then he called me back," Tami remembers. "And he said, 'Tami, they're alive.' And I just fell to the ground crying, 'They're alive. They're alive.'"

A small good comes from a large evil

The earthquake took about 250,000 lives. But, with their heads bowed, Kermit and Tami also hoped it might open a window for five.

Tami walked around with a telephone attached to her ear. That, or they were on the Internet. They learned that legislators from Ohio, Pennsylvania and upstate New York were trying to pry all kinds of children out of Haiti, which was an uplifting sign. But the brighter news came three days after the quake when Janet Napolitano, the U.S. secretary of Homeland Security, announced that the U.S. would be granting humanitarian parole to children already in the process of being adopted.

Tami and Kermit understood that was the ticket. They called the State Department to get all five kids on the list and began frantically filling out paperwork. But when they checked back a few days later, the computer didn't show the kids' names. They wanted to pull their hair out. They resubmitted the paperwork and solicited the help of legislators Dianne Feinstein and Maxine Waters of California. Finally, 12 days after the earthquake, they were given word that the kids were being flown to Florida.

They made arrangements to fly and meet them, but when Tami called the State Department to confirm that the kids' travel documents were set, once again none of the five was on the travel list. The U.S. government asked her to refile the paperwork, which would mean another week's delay, and Tami broke down sobbing. Once more, she pleaded her case, and this time the State Department apologized. It said it had found four of the kids' travel docs.

"Just four?" Tami asked.

"Yes, just four."

That meant that one of the kids wasn't coming, that one of them still would be stuck in a place where there was rampant disease, dead bodies, and little food or clean water.

Clifton.

Learning the meaning of 'interminable'

Time was of the essence. UNICEF was livid that a Dutch group had hastily flown a flock of children out of the country, and to prevent child trafficking, the government planned to restrict all travel out of Haiti. Clifton conceivably could be stuck in the mayhem indefinitely, and Tami told Kermit she might need to fly to Port-au-Prince and escort him out herself.

She couldn't understand how he had fallen through the cracks. His adoption papers had been filed first. He'd been the catalyst for Tami and Kermit's marriage. He'd given Kermit hope again. He'd started it all. And now he was in limbo at the American embassy in Port-au-Prince, while his brothers and sisters were at the airport.

Earlier, Tami had been given the phone number of a high-ranking official at the Department of Homeland Security, but she'd been told to call only in an emergency. Now was that moment. She dialed the official, who told her Clifton's siblings would arrive in Miami on Jan. 25. But the official needed more time on Clifton, probably a couple of days. Tami was near her breaking point. Haiti was still having 6.0 magnitude aftershocks. They decided Kermit would meet the four siblings in Miami and a friend of Tami's who owned a private plane would fly her to the Dominican Republic. From there, she'd get to Port-au-Prince, find Clifton and bring him home.

But an hour later, a woman from the State Department called. "Are you sitting down, Tami?"

"Should I be?"

"I just wanted you to know that all of your kids are on planes headed for Orlando. You need to go there instead of Miami."

"Are they together?"

"No. Four of them are on a military transport plane, and Clifton made a cargo plane. But they're on their way. Go get your kids."

Kermit and Tami caught a red-eye to Orlando that night, arriving at 8:30 the morning of the 26th. They were escorted to a makeshift office set up by Homeland Security, grilled about their intentions and asked to turn over paperwork. The U.S. government had been warned that unauthorized civilians were trying to grab stray Haitian kids and take them home. So Tami and Kermit found themselves locked down for six hours.

By 4 that afternoon, they were finally directed to a large customs area where about 100 people were sitting down. Around 40 of them were Haitian kids, and as the couple entered the room, 40 heads started turning their way.

Then they heard, "Dad!"

The oldest boy, 14-year-old Jameson, had seen Kermit first. An instant later, 9-year-old Semfia, the younger girl, was jumping into Kermit's arms and 10-year-old Zachary, the youngest boy, had attached himself to Kermit's leg. Tami got the leftovers -- 16-year-old Manoucheka, the older girl, and 11-year-old Clifton.

Kermit checked to see whether the kids had any cuts or scrapes. He looked into their eyes to make sure they could see. He was bawling as he held them. There was no doubt among the Homeland Security employees -- these were Kermit and Tami's children.

"It was the best day I'd ever had -- since 1984," Kermit says.

A second chance to smile

All the Alexanders -- all seven of them -- flew home to California the next day. They didn't mean to cause a scene, but the kids walked single file through the Orlando terminal behind Tami, like five little ducklings. Kermit, the proud papa, trailed behind them all, counting heads, grinning.

The previous night, the kids had begun to share snippets of their ordeal. They'd slept outside after the earthquake, frightened of the aftershocks. They hadn't had a bath since Jan. 12. At their hotel, Tami asked whether they wanted to take a hot shower, but they'd never heard of such a thing. The water in Haiti was always cold, and when they took their first American shower, they didn't want to get out. It was heaven. They wanted to take two.

All of the amenities were new to them. They had never flown in a commercial jet before and were shocked to see a bathroom on the plane. They had never slept on real mattresses, either. In Haiti, the beds were made of cardboard. That, or they'd sleep on a pile of clothes on the floor. So their first American hotel was sweet culture shock. And when they arrived late at night at their new house in Riverside, on the cul-de-sac, they fell fast asleep in a matter of minutes -- on thick mattresses -- curious about what was in store for them in the morning.

When they awoke and took a look around the house, they went bonkers.

"This is ours?" Jameson asked.

"This is yours."

The kids went room to room, digging through every drawer, every closet. They touched every piece of clothing, sat in every chair, opened every cupboard full of food, the whole time clamoring, "This is ours? This is ours?"

They bolted to their expansive backyard and found the basketball court and the trampoline and the pool. They spent the entire day in the sun, and while they were outside, Tami and Kermit happened to peek into the kids' rooms. Every bed was perfectly made. "Could've bounced a quarter off them," Tami says.

There were so many questions to ask about the earthquake, but Tami and Kermit didn't push the kids, reasoning that they would open up when they were ready. Finally, Clifton shared that he'd been playing soccer when the quake hit and he had simply lain down on the ground while he heard other children screaming. "A lot of people die," he said.

As for the other four, who had been closer to the epicenter, they were lucky their orphanage had sturdier buildings. Jameson and Zachary were playing basketball outside at the time of the quake, which was a blessing. Manoucheka was in the baby nursery and ran outside carrying some of the infants. Semfia was eating rice and couldn't understand why she couldn't get the spoon to go in her mouth. They each had a tale.

After a week at home to settle in, Kermit began walking the children to school every day. Before long, other kids were inviting them over for playdates, and they were becoming more Americanized by the day. They liked pizza, not broccoli. They rode their bikes. They were fascinated by roller skating. They stayed up late. Semfia learned every song from "High School Musical" and wanted to be a diva when she grew up. Jameson wanted to be a soccer pro. Zachary, who cooked dinner every night with Tami, planned to be a businessman. Manoucheka wanted to be a pediatrician. And Clifton intended to be a pastor, like Kermit's grandfather.

As the kids' diet and nourishment improved, the changes in them were striking. Clifton grew an inch in the first two months. Semfia grew maybe two. Jameson grew maybe three and began towering over everyone. They were all immersed in sports. Semfia was a budding soccer player and sprinter. Manoucheka became enamored of volleyball. As for the boys, basketball -- not soccer -- became their regular game du jour. Clifton rooted for Kobe; Jameson and Zachary preferred LeBron. The three of them even began playing an imaginary Lakers-Cavaliers final in the backyard.

Kermit also showed them highlights of his 49ers days, and loved it that they didn't know who Gale Sayers and George Halas were. He also watched Clifton eat cotton candy for the first time -- the boy was stumped as to why the candy disappeared in his mouth -- and it made him think again of Tiequon Cox. Clifton was Kermit's do-over, his second chance at life. This wasn't lost on the old pro.

He would get up every morning about 5:30, while the rest of the house was sleeping, and he'd meditate and think about Ebora. Five-thirty in the morning is when they used to have their coffee together, and he'd talk to her each morning at dawn now and thank her for making this happen. Because he knew she had made this happen.

He only wanted to be the parent she had been, and, at every one of those 5:30 meditations, he would pray that he could be a rock for his kids the same way he had been a rock before 1984. He and his mom used to talk back then about saving the world, and now he at least had a chance to save his own sliver of it. He had rescued five kids. Or maybe five kids had rescued him. Either way, his house was full, and nothing was better than a full home.

He hoped the children would someday feel about him the same way he felt about Ebora. But it couldn't be rushed; it had to happen organically.

And then the earth moved again.

On Easter Sunday, in midafternoon, a 7.2 magnitude earthquake rocked Baja California, a few hours south of the cul-de-sac. The ground rolled beneath the house, and Kermit jumped up, afraid the kids would have hysterical flashbacks. He rushed to see where they were, and found four of them outside playing basketball, completely unaware. They hadn't even felt a bounce.

Only Manoucheka, his oldest daughter, had been inside to feel the house shake. She ran into Kermit's arms and asked him, "Aren't you afraid, Dad?"

"No, we'll be fine."

"If you're OK, I'm OK," she said, exhaling.

The two of them then sat down on the couch, and she went back to writing in her journal. Kermit stared straight ahead. He could hear the other kids squealing and playing. The guilt was nowhere in him now. Everybody was safe and sound. Safe and sound.

Tom Friend is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine.

Join the conversation about "Kermit's Song."